Willehalm: King Of The Jews?

Introduction To The

Fourth, British Edition, Including

The Kardeiz Saga To Recall The Anthroposophical Society

|

H |

ow The Grail Sites Were Found – Wolfram von Eschenbach And The Reality

Of The Grail has been presented this summer

of 2001 in various private and public (town) libraries in North America

(Montreal, Canada and New England) and is now, God willing, to be launched in a

fourth edition (with British spelling) in Great Britain in the Rudolf Steiner

House in London on October 26. In the previous introduction to the third, North

American edition we have already prepared English-speaking readers for the

somewhat surprising, if not startling fact that a 9th century King

Arthur is located by Werner Greub on the bank of the Birs river (Wolfram’s

Plimizoel) flowing into the Rhine near Basle, Switzerland.*

Another minor culture shock for the British reader may well be that he or she

will search in vain for any actual Grail sites specifically related to Wolfram’s

Parzival and Willehalm in the United Kingdom and Ireland – these

sites are all to be found, as he or she might say, “on the continent”. Yet,

this does not by any means signify that “exports” from Great Britain play no

role in this book, on the contrary.

Alcuin

To mention just three that come to mind as having something to do with

Great Britain and the English and Celtic spirit: first of all there is the

great scholar Alcuin, the representative of Celtic, Scottish-Irish

Christianity, who was born in York and who, as the real spiritual leader of the

Carolingian empire of Charlemagne, was also the teacher of Willehalm, the

historical William of Orange and Toulouse. It was Alcuin who prepared Willehalm

for his Grail quest and his ultimate role as spiritus rector of the Grail

events of the 9th century as described in this book.

Count Cagliostro

Then there is the Italian-born, cosmopolitan Count Cagliostro, by many

–unjustly –considered to be just a charlatan, who in these pages is portrayed

as coming from London in 1782 with his wife, the beautiful Serafinia Feliciana, and his friend the painter Lauterburg to help with the design and

laying of the English Garden in the Arlesheim Hermitage in Switzerland,

including a Freemason meeting hall in the “Cave of Death and Resurrection”,

that Werner Greub identifies as the cave of the hermit Trevrizent, located not

far from the Grail castle Munsalvaesche on the Hornichopf Hill.

Walter Johannes Stein

Finally, the anthroposophist and personal student of Rudolf Steiner,

Walter Johannes Stein deserves to be mentioned in this context, for Stein,

although born in Austria (Vienna, 1891), lived the latter part of his life in

London where he was advisor to his friend, the well-known industrialist, writer

and anthroposophist D.N. Dunlop and, to a lesser extent, to Winston Churchill

during the war. Werner Greub quotes from Stein’s book The Ninth Century –

World History in the Light of the Holy Grail in order to illustrate his

point that Rudolf Steiner, the founder of anthroposophy or science of the

Grail, was the first one to distinguish between the microcosmic Christianity of

the French Perceval by Chrétien de Troyes and the macrocosmic

Christianity of Parzival by Wolfram von Eschenbach, a distinction that

is much enlarged upon and deepened in this book.

The Spear Of

Destiny

There is of course another English connection mentioned briefly in

appendix V entitled “Beyond Truth and Reality – Two Misleading Books For Grail

Seekers” of this English translation. In this appendix an attempt has been made

to refute the allegations made by the anthroposophical historian and (deceased)

critic Christoph Lindenberg in his review by that name that this book by Werner

Greub is “beyond truth and reality”.

The other “misleading”

book in this review by Lindenberg is namely the bestseller The Spear Of

Destiny (first published in Great Britain in 1973) by a student of Walter

Johannes Stein, Trevor Ravenscroft. His book is largely based on inside

information from his deceased teacher Stein, in which he juxtaposes Adolf

Hitler against Rudolf Steiner, claiming that his book was the continuation of

Stein’s standard work on the Ninth Century. Contrary to Greub’s work, which supplies detailed geographical

evidence in order to prove that Wolfram von Eschenbach was describing factual

conditions that can be corroborated by on the spot inspection, Ravenscroft’s

book was apparently written as a historical novel and only afterwards, in order

to boost sales, promoted as depicting real history, something that Lindenberg

did not know or at least did not point out.

As such, it is not surprising that, as Lindenberg takes pains to show,

many details in Ravenscroft’s dramatic novel are false. He indicates, for

example, that many blank spaces in Hitler’s biography that at the time of

Ravenscroft’s writing were still unknown, have in the mean time been filled in.

Yet this oversight applies to Lindenberg as well, in the sense that at least

one of his point-blank denials that Ravenscroft was telling the truth must, on

the basis of what since then has become known, be retracted or at least

modified. This concerns, as Lindenberg writes in his review, “one of the

especially grave, false claims [that Ravenscroft makes] namely the statement

that the deceased Chief of the General Staff [of the German army] von Moltke

would have relayed – through the tongue of his wife, who supposedly possessed

the gift of speaking in tongues – messages to friends of the family of von

Moltke concerning the further course of the 20th century, is a

fabrication.” However, as the second volume of post-mortem documents on von

Moltke’s life and work, published by Thomas Meyer in 1993 *

show: The deceased General von Moltke did indeed send post-mortem letters to

his wife on the future course of the 20th century, only the medium

in this case was not his clairvoyant wife, but Rudolf Steiner.

Be that as it may, Lindenberg’s scathing review of The

Spear of Destiny did not prevent it from becoming a best-seller, while his

dismissal of How The Grail Sites Were Found, being a book originally

written in German, had more success: It prompted many anthroposophists, for

whom it was primarily (but not exclusively) written, to dismiss it as well. –

including for a while the writer of these lines. Moreover, as already referred

to in the first introduction, it apparently prevented the leadership of the

Goetheanum from publishing, as originally announced in the first volume, the

two remaining ones of Werner Greub’s projected Grail trilogy Willehalm Kyot

– Wolfram von Eschenbach ‘s Source and From Grail Christianity to Rudolf

Steiner’s Anthroposophy, which were then later published as manuscripts by

the Willehalm Institute in Amsterdam (see appendix 7) and in 2003 and 2004 by

his son Dr Markus Greub.

Holy Blood and

the Holy Grail

An even bigger best-seller than The Spear Of Destiny in England

and elsewhere was of course Holy Blood and the Holy Grail by Baigent,

Leigh and Lincoln, first published in the United Kingdom on 1982 and

republished with a postscript in 1996. In our previous introductions as well as

in the footnotes to appendix III The Arlesheim Hermitage as Grail Landscape

we have already referred to this book as well as to the multitude of sequels

that it spawned or for which it set the stage, such as the books by Michael

Bradley and Sir Lawrence Gardner.

In our first

introduction How This Publication Came About credit was given to the

astrosopher Robert Powell “who in the summer of 1979 published an extract from

this present volume entitled The Pre-Christian Grail Tradition of the Three

Kings in his (now defunct) Mercury Star Journal vol. 5, no. 2, that was

mentioned in the bestseller Holy Blood and the Holy Grail in connection

with Willehalm-Kyot.” Indeed, Willehalm plays a prominent role in the Holy

Blood and the Holy Grail where he is usually called Guillem of Gellone, but

also given other titles such as Comte de Razès and even King of the Jewish

principality Septimania in the south of France, the Languedoc. The reference to

Guillem occurs in chapter 11 The Holy Grail in the section The Story

of Wolfram von Eschenbach on page 317. This occurs after it is claimed,

without any evidence or footnote – not altogether untypical for this book –that

“the [Grail] Castle [Munsalvaesche] itself is situated in the Pyrenees”,

suggesting that this is somehow to be gleaned from Wolfram’s third (unfinished)

work Der Junge Titurel, which it is definitely not.

Then the passage continues:

In addition to Der Junge

Titurel, Wolfram left another work unfinished at his death – the poem known

as Willehalm, whose protagonist is Guillem de Gellone, Merowingian ruler of the

ninth-century principality straddling the Pyrenees. Guillem is said to be

associated with the Grail family.

Here there is a footnote: “Greub, ‘The Pre-Christian Grail Tradition’,

p. 68.” In the bibliography under Greub, W., it is then mentioned that this

article from the Mercury Star Journal is an extract from Wolfram von

Eschenbach und die Wirklichkeit des Grals. This extract is probably taken from

the Chapter Kyot the Provençal, long after Kyot has been identified by

Greub as Willehalm or Guillem of Gellone, something which apparently the

authors of the Holy Blood… overlooked or did not see fit to mention. In

the Postscript to the 1996 edition of the Holy Blood…(on p. 475) Wolfram

himself is given as the source, again without any reference, for something, which as

Werner Greub does indeed show to be the case, but for which no or even wrong

evidence is given:

Guillam (sic) was also cited by Wolfram von Eschenbach

as a member of the Grail family.

After devoting a sub-section to “Prince Guillem, Comte

de Razès” in the chapter “The Long-haired Monarchs”, the Holy Blood and the

Holy Grail relates the following about Willehalm in the one to last chapter

“The Grail Dynasty”:

Despite subsequent attempts to conceal it, modern

scholarship and research have proved Guillem’s Judaism beyond dispute. Even in

romances – where he figures as Guillaume, Prince of Orange – he is fluent in

both Hebrew and Arabic. The device on his shield is the same as that of the

Eastern ‘exilarchs’ – the Lion of Judah, the tribe to which the house of David

and subsequently Jesus, belonged. He is nicknamed ‘Hook-Nose’. And even amidst

campaigns, he takes pains to observe the Sabbath and the Judaic Feast of the

Tabernacles…He was not only a practicing Jew, however. He was also a

Merowingian. And through Wolfram von Eschenbach’s poem, he and his family are

associated with the Holy Grail.

The authors of the above base themselves on a scholarly and voluminous

work entitled A Jewish Princedom in Feudal France 768-900 by Arthur J.

Zuckerman, Adjunct Professor of History and Director of the Hillel Foundation

at the City College of New York and Professor of medieval Civilization at the

Reconstructionist Rabbinical College, a work that we have already referred to

in our refutation of Lindenberg’s review in the appendix. Zuckerman’s erudite

research report was published in 1972 by Columbia University Press New York and

London with a grant from the Memorial Foundation for Jewish Culture and an

additional grant from the Kohut Foundation, and edited under the auspices of

the Centre for Israel and Jewish Studies at Columbia University.

We mention the

impressive list of credentials and financial backers of this work in order to

indicate that we are not simply dealing here with obscure literary and

religious skirmishes in an academic ivory tower, but with fundamental issues

and values underlying our Western civilisation of which indeed Willehalm is an

icon.

Willehalm, King of the Jews?

Is Willehalm of noble Jewish origin from the House of David? This indeed

is possible, but refers only to his background, his bloodline. And as we have

mentioned with respect to the greatest miracle that Trevrizent calls Parzival’s

revolutionary attainment of the Grail kingship – the bloodline has outlived its

significance as a determining factor for the spiritual development of one’s

personality in general and for the justification of fulfilling the office and function

of kingship in particular. For the purpose of the latter, the new royal art of

social organics has become the guiding principle with which to nominate, select

and “crown” candidates for this high office.

The arguments

for the claim, however, that Willehalm was also a practicing Jew, or

even King of the Jews, such as his nickname “Hook-nose” and the

interpreted statements from the romances, whereby probably the French chansons

de geste are meant, and other sources do not hold – whereby it should be remembered

that according to the Gospel of John (Ch. 18 and 19) the title King of the Jews

was given to Jesus Christ, who denied it, by Pontius Pilate and to the chagrin

of the Chief Priests. Willehalm’s nickname in French was “Court Nez” and had

nothing to do with a hooked nose, but referred to the missing tip of his nose,

a loss he incurred in combat from the slash of a sword. And the degree of

reliability of the romances are in this book shown to be rather scanty, as are

the reports of the court and church historians of that time, who were all more

or less biased in favour of their respective ‘employer’, a conclusion that

Zuckerman in his book also reaches.

But all these are relatively minor points in

comparison to the convincing image that Werner Greub, immaculately based on the

work of Wolfram von Eschenbach, conveys in Part I of this book. Willehalm-Kyot

is portrayed as the most advanced, all-rounded and courageous army-commander,

knight, scholar and Grail Christian of his time, well versed in the civilisations

of the ancient East and the newly emerging West, who was able to convert the

Arabian princess Arabel to Christianity just because of his all-encompassing,

macrocosmic Grail or Celtic Christianity that had preserved the link to the

ancients, the pre-Christian tradition of the Three Kings. And as supreme

commander of the Carolingian army at the southern flank of the threatened

Empire, he had successfully resisted the take-over and subjugation of Europe by

the Moors, thereby setting the stage for the new universal spiritual impulse

brought on by Parzival under the Star of Munsalvaesche on free Christian soil,

an event in which as Kyot the Provençal he himself assumed the role of spiritus

rector, and as Kyot of Katelangen became one of the leading actors in this

Christian mystery drama.

Greub ends his work with a reference to the prologue

to Wolfram’s Willehalm, an appeal to the Holy Trinity, an exclusively

Christian concept, to assist him in composing his hymn:

May the help of Thy loving Kindness inspire my heart

and mind aright and grant me skill enough to praise in Thy Name a knight who

never forgot Thee. Even if he merited Thy displeasure by sinful action, Thy

Mercy knew how to guide him to work, of such a kind that, with manly courage at

his disposal and by means of Thy Grace, he was capable of making amends. Thy

Help often saved him from peril. He risked a twofold death, of the soul and of

the body too, and frequently suffered anguish through the love of a woman.

This may be sufficient to indicate,

if not to prove that, based on the findings of this remarkable book on the

personality and work of Wolfram von Eschenbach, the answer to the question that

we placed at the head of this introduction must be negative: Willehalm was not

a Jewish King, but a Christian Saint.

Towards A Willehalm Society

Now it is obvious that with the

above remarks and passages, however, the discussion and debate about the issues

at hand and indeed many others that are raised by this book has only at best

been opened and needs to be continued in an appropriate form and forum. In his

foreword to this present volume the former president of the General

Anthroposophical Society Rudolf Grosse calls for a thorough scientific

discussion on the merits of this book, and throughout it and especially in the

epilogue, Werner Greub invites scholars to enter the many new avenues of

research that his book opens up. None of this has to my knowledge really been

taken up yet; indeed since its publication in 1974 not one word has been “wasted”

on it, apart of course from the devastating review by Lindenberg and the notice

of Greub’s death, in any of the official organs of the General Anthroposophical

Society or in any of its branches throughout the world.*

This is thus one of the reasons, indeed justifications for the founding of a

Willehalm Society for Grail Research, Royal Art and Social Organics, as

suggested in the introduction to the first edition. Such an interested circle

of supporting friends centred on a spiritually active Institute with a

publication journal and regular newsletter in the form and spirit of the

Anthroposophical Society with its core the School of Spiritual Science has

existed in a small, but seminal form in the Netherlands since 1990. However, in

order to realize any of the objectives and research projects raised by this

book, much more needs to be done, hence my present plea. Accordingly, this was

part of the subject and indeed motive of my talks, backed up by the various

book presentations to members and friends of the Anthroposophical Society this

summer at the Rudolf Steiner library Ghent NY and in Montreal, Canada; the last

talk being on September 10, 2001 to a closed meeting of the English and French

speaking groups of the Anthroposophical Society in Montreal.

The September

11 Disaster en de Kardeiz Saga

This brings me to the disaster of

September 11, for it does not seem appropriate to end this introduction to the

British edition without enlarging somewhat on the initial reaction I wrote in

Montreal to this disaster in the light of this book, its background and the

substance of recent talks and presentations held in North America. ** This initial reaction, placed in a

footnote to the Postscript of the third (North American) introduction and dated

September 19 went as follows:

Never has the need been greater for a strong mediating

force of the middle between two hostile, opposite camps that are both convinced

that they are involved in a (holy) war, a crusade to eradicate evil, i.e. each

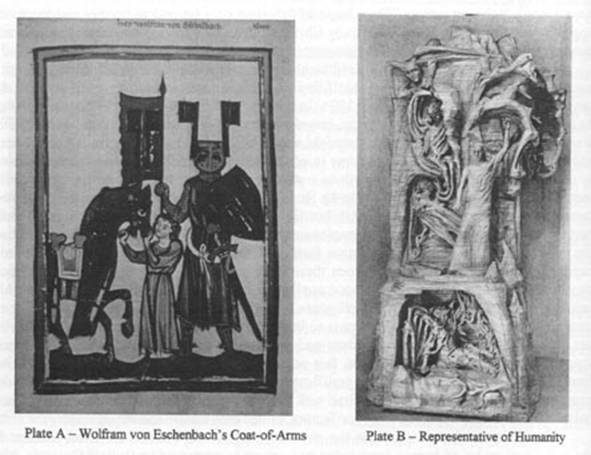

other. As portrayed by the symbol on Wolfram von Eschenbach’s coat-of-arms,

this task of balancing, i.e. neutralizing two opposing (divine) forces has

always been the task of Grail knights.

Is it too much to say that this tragedy could have been averted, if

there had been a really new Grail Community centred around a modern Grail

castle Munsalvaesche in the world and therefore also in America? Averted in the sense that the conflict could

have been diverted from the physical arena to the soul realm where the

differences could have been ironed out by peaceful, spiritual means.

Now the first thing that needs to

be said, indeed admitted, is that the very occurrence of this man-made

disaster, this horrific example of man’s inhumanity to man, is a tragic indication

of the failure of politics and ultimately of the spiritual-cultural sphere of

the social organism on the planet. For as Rudolf Steiner has pointed out in his

essay Anthroposophy and The Social Question where he developed his

fundamental social law, practical ideas are the very life-sustaining sustenance

for this social organism, without them the inevitable result will be disaster,

hunger, chaos and in the end war. The individual, the human body, can indeed be

helped by giving him or her bread, a community, i.e. a social body, can only be

aided by helping it to attain a viable worldview. Since this outbreak of war

and the ensuing bloodshed and suffering of many innocent people on both sides

is indicative of the moral bankruptcy and failure of the spiritual life, then

this also applies to the General Anthroposophical Society and its present

leadership at the Goetheanum in Dornach, Switzerland, as well as to the various

national Anthroposophical Societies and related groups, indeed the Willehalm

Institute included, in as far as these organisations are part of the present

impotent spiritual life of mankind on earth.

A corollary to the

above fundamental law is that the individual human being or any number of them

can be destroyed, but that the human being as such, humanity itself can only be

destroyed by eradicating the true, good and beautiful image of that humanity

and a human society constructed in its image. This anti-anthroposophy, this

dehumanisation is indeed the “highest” form of slouching terrorism that is the

least noticed for where and what it is. Now, this structural and principled

destruction of humanity and a humane society in its image has been exactly what

modern, materialistic science, in spite of its undeniable technical advances,

has been doing; and radically complementing and revising this basically

inhuman, or at least incomplete science of man and mankind is exactly what

Rudolf Steiner has brought to bear with his anthroposophy or science of the

Grail.

The mission of

spreading and deepening this true image of man and his society he entrusted to

the Anthroposophical Society, which was founded anew in 1923 and to its centre

of research and development, the Goetheanum, Free University of Spiritual

Science, which, as we have seen, in 1974 published, but then dropped this

present volume and its sequels. Yet in spite of the individual efforts of many

well-meaning and indeed brilliant anthroposophists, often working in complete

isolation and abject poverty, the leadership of the newly refounded

Anthroposophical Society already before the early death of Rudolf Steiner in

1925 has in general failed to observe and fulfil its one and only task: to

realise the original statutes of this Society statutes (later called

principles) as an all-embracing new principle of civilisation called social

organics that is destined to supersede the more than 2000 year old democratic

principle. Not only has it failed to do this, but it has for the last twenty

odd years resisted and suppressed all attempts by individuals, including the

author, and small groups to uncover and correct this. Only recently, in the

face of increasing pressure and dissent, has the leadership begun to face this

constitutional dead-lock, although it is far from acknowledging that this is

the main structural cause for the state of world-wide paralysis,

analogous to the sick Fischer king Anfortas, in which the Anthroposophical

Society finds itself. What we have here is thus a general human society which

has been entrusted with the true image of man and mankind on earth, but which

has not managed to remain true to itself and therefore cannot attain its

mission to become a vanguard of the new principle of civilization! Before

anything else can be put in order and healed in this world, it must be the Anthroposophical

Society.

In effect, what we

have been doing here is nothing else than asking the Parzival question:

“Uncle”, – in this case the Anthroposophical Society and its leadership, and in

a general sense the spiritual life of humanity – “What ails you?” Yet, since

this is not an individual matter, but an issue facing a community at large,

this Parzival-question needs to be asked by at least one fifth of its members,

i.e. some 10.000 anthroposophists all over the world, for this is the quorum

according to Swiss Civil law (on associations) needed to support the idea of

holding an extra-ordinary General Meeting of the Anthroposophical Society – the

first such meeting since 1923, when the Anthroposophical Society was refounded

in Dornach, Switzerland. For since 1925 annual meetings have been held of the

administrative and economic pendant of the Anthroposophical Society, namely the

General Anthroposophical Society, Inc. These two similar sounding social bodies

were long considered to be one and the same. In reality they were conceived as

different in quality from each other, albeit related, as for example Grail

knights-of-the word such as Parzival on the one hand and Arthurian

knights-of-the sword such as Gawain on the other, the former more heavenly, the

latter more earthly orientated. Epistemologically speaking they are as

different from each other as mental pictures are from pure concepts. The former

being individualised concepts applied to a percept in an act of knowledge and

forming the basis of administration; the latter being universal ideas that have

not been applied to percepts and constituting the realm in which social design,

royal art can be practiced.*.

Now, as Part II

entitled Parzival of this book demonstrates, Parzifal asked his question

with which he redeemed Anfortas and became Grail King on Whitsuntide, May 12,

848 in the Grail castle Munsalvaesche in the Arlesheim Hermitage. On April 8,

2001 a Parzifal question in the above communal sense was put by the author in

the form of a motion to the General Assembly of the General Anthroposophical

Society at the Goetheanum in nearby Dornach as the first act of a real-life

communal mystery play entitled the Kardeiz Saga to Review, Recall and

Restore the Anthroposophical Society.**

The historical basis for this play is inspired by this very book by Werner

Greub, for in it Kardeiz is shown to be the second son of Parzival who as a

youth was already crowned King on Whitsuntide May 13, 848 in Dornach and given

the task of regaining the lands and towns (Waleis, Norgals, Kanvoleiz,

Kingrivals, Anschouwe and Bealzenan, all situated in present-day Alsace,

France) that were taken away from his father by the usurper Lahelin, a task

which he, after having been educated by his uncle Willehalm-Kyot, fulfilled admirably.

The historic parallels implied by the Kardeiz Saga – a realm of royal art has

been usurped and must be liberated and restored to its original state in order

to fulfil its mission to advance humanity to a true image or concept of itself

– may have by now become apparent; for the details I refer to my foreword to

the social-aesthetic study The Principles of The Anthroposophical Society,

which forms the more spiritual basis for the Kardeiz Saga. What remains here is

to attempt to further substantiate in what sense this Saga can be seen as a

modern Grail task and what relevance it has for a post September 11 world

situation

For that we call to

aid a perspective from Walter Johannes Stein mentioned in the book by the Dutch

writer Willem Frederik Veltman Tempel en Graal (Temple and Grail, published by Hesperia in Rotterdam, 1989; not

translated). In a chapter The Mystery of Gold on the three historic

grades of chivalry, it is developed that the Grail impulse of the 20th

century – and no doubt also for the 21st – lies in transforming the

driving force of the world economy from egoism to altruism. The first one is

the grade of Faith (Peter), the second one of Hope (James), both lying in the

past, while the current and future one is the grade of Charity or Love (John).

Veltman writes: “This Grade of John can only be realized today and has to do

with a world economy based on a truly Christian love. But for the time being,

the world economy as a world power is still developing in an opposite

direction.”

How this can be

considered a Grail task – the harmonisation of two polarities through a middle

force – has been shown by Rudolf Steiner in his lectures and seminars on World

Economy in Dornach 1924. In the first of these 14 lectures he states that what

he is about deliver is the new language, based on a new way of thinking, with

which to present social organics, the idea of the threefold nature of the

social organism, in the near future and that it is above all necessary to come

to an understanding of the concept social

organism as consisting of humanity and the earth as a whole, as one. This

social organism or environment is – this follows from other works by Rudolf

Steiner in concordance with the New Testament – in essence the body of Christ,

but He can only properly incarnate into this whole earth, if we as humanity

practice and implement Rudolf Steiner’s World

Economy by creating the right balance between the production factors of the

social organism: nature, labour and capital (spirit). The interaction between these

three production factors constitutes the two ways that economic values arise:

labour applied to nature bringing about the more earthly value of

transubstantiation; spirit (intelligence) applied to labour the more heavenly

value of incarnation. The cardinal question here is to bring these two ways of

creating economic values into harmony by producers, traders and consumers,

united in economic associations spanned across the globe, so that just, fair

prices can come about. This radical alternative form of globalisation is the

Christian justification for the threefold social order or social organics, and

can be seen as a modern Grail task because, again, it is question of creating a

just balance between two opposing forces or factors, in this case nature and

capital (spirit).

This collective

balancing act in the physical, outer world has its individual pendant in the

individual realm of human knowledge and action as portrayed in Rudolf Steiner’s

Philosophy of Spiritual Activity. For knowledge is the synthesis of a

given percept mediated to us by our senses with the proper, corresponding

concept supplied by our own act of thinking, while action, a human deed is the

synthesis of motive and driving force.

This Grail task, as

symbolized by Wolfram’s coat-of-arms (see plate A) is portrayed in another way

by Rudolf Steiner in his wooden sculpture, made with the assistance of among

others the English sculptress Edith Maryon, entitled Representative of

Humanity. It shows a trinity: a solid and balanced human figure in the

middle separating and harmonizing two opposing forces or beings: Ahriman or

Satan, the cynical oppressor being held and chained down to the earth and

Lucifer or the Devil, the enticer in the heights misleading to a brilliance

without soul warmth (see plate B). This 9 metre high structure was meant by

Rudolf Steiner to stand in and form the background of all the proceedings in

the first Goetheanum, which like the Grail castle Munsalvaesche was a theatre

for the staging of Christian mystery plays. It escaped being burned down to the

ground when this first Goetheanum, an all wooden structure with two

interlocking domes went up in flames during New Year’s eve 1922, but instead of

being given this prominence is now stored in the attic of the second Goetheanum,

where, far away from the activities on stage in the big hall down below, it can

be seen at certain hours – a deviation from the intention of its maker which,

it must be said, speaks, even cries out for itself.

By now it may be clear that this

Grail motive of a trinity of active neutrality is the major composition

principle of Rudolf Steiner’s anthroposophy, justifying its alternative name:

science of the Grail. We encounter this principle again in the architectural

design of the second Goetheanum, in which two symmetrical sidewalls running

north and south connect a polarity of a steep vertical wall to the east with a

gently outward sloping wall to the west.

And we see it also in the

composition of the statutes (principles) of the newly founded Anthroposophical

Society and the corresponding Foundation Stone Mediation, which Rudolf Steiner

offered to lay down in the hearts and minds of the nucleus of some 7 to 800

anthroposophists from all over the world who had gathered in Dornach in 1923

during the so-called Christmas Foundation Conference to call this first general

(universal) human knowledge-based society on earth further into being. This

Anthroposophical Society was, according to its first of 15 statutes

(principles), meant to be “a union of people who wish to cultivate the life of

soul in the individual as well as in human society on the basis of a true

knowledge of the spiritual world.” In

the process of realizing this universal charter of a society of free spirits –

according to Rudolf Steiner the one and only task of the leadership – its

members can unite and elevate themselves to a level of awareness of their

higher selves where they can receive the representative of humanity in their

own ranks and accordingly constitute the new Grail community. Like the statute

of the representative of humanity that was to overlook this process, this new

Grail community will consist of a strong and solid middle holding Lucifer

(extreme ingrowths, sectarianism, dogmatism) as well as Ahriman (power plays, con

tricks, party politics) at bay.

These are the living

conditions, as laid down in an archetypal fashion in the original statutes of

the Anthroposophical Society, under which the Parzival question, asked in

concert by a community, can have the healing effect on it that it did on

Anfortas that Whitsuntide on May 12, 848 in Arlesheim when, as Wolfram towards

the end of his Parzival reports: “He Who for St Sylvester’s sake bade a

bull return from death to life and go, and Lazarus stand up, now helped

Anfortas to become whole and well again.”

To re-enact this real-life communal mystery play, ideally and to begin

with on the location of the original Grail sites in Dornach/Arlesheim in

Grail Sites of Royal Art in the Future?

The newly discovered Grails sites

will then not only enter the history books as having been found, but founded

anew and harbouring a healing impulse for the future. For the resulting

world-wide “Union of People” can then become that strong middle force of active

neutrality that was mentioned in my initial reaction to the September 11

disaster in order to help make the world “whole and well again.” The history

books will then also thankfully note that a violent clash of civilisations has

been diverted in the sense that bearers of conflicting worldviews and religions

can iron out their divisive differences, problems and obstacles in newly

constituted Olympic Games of The Spirit with the participants competing for the

best ideas toward the solutions of the problems facing mankind and the

earth. Finally, the writing of history

books will remain necessary, for history – contrary to what has been claimed –

will not have come to an end, for want of any alternative to the present

liberal, capitalist based democracies, since the demise of communism. For an

all-embracing worldview, a reunion of art, science and religion is waiting in

the wings to make its long over-due appearance; it is called anthroposophy,

science of the Grail, its social component is social organics. A new Royal art

can lead the way.

Robert J. Kelder,

Willehalm Institute,

Acknowledgement

My thanks go to Richard Roe from

* For an introduction

to King Arthur in

* Helmuth von Moltke

1848-1916 – Dokumente zu Seinem Leben und Wirken, Band 2 Briefe von Rudolf

Steiner an Helmuth und Eliza von Moltke: Perseus Verlag Basel 1993. A slightly abbreviated

version of the first and second volume of this have been translated into

English and was published under the title Light For The New Millennium by

the Rudolf Steiner Press,

* One example: On the

occasion of Werner Greub's death on

** Next

to this present volume, two new editions of translations of works by Herbert

Witzenmann, already referred to in the first introduction, were presented: The

Just Price – World Economy as Social Organics and The Principles of the

Anthroposophical Society with a Foreword Introducing the Kardeiz Saga to Recall

the Anthroposophical Society. Both of them included extensive introductions

on which the following remarks in connection with the September 11 disaster are

partly based and which need to be consulted by those who want to pursue the

matter further. Here only a broad outline can be given.

* For this epistemological distinction see Rudolf Steiner's Philosophy of

Spiritual Activity and Herbert Witzenmann's social-aesthetic study Gestalten

oder Verwalten / Rudolf Steiners Sozialorganik – ein neues

Zivilisations-prinzip (Dornach, 1986) (To Create or Administrate – Rudolf

Steiner's Social Organics/ A New Principle of Civilization) not yet translated.

** This motion with the motivation for it was printed in full in the

German issue of the Goetheanum News for Members (Nachrichtenblatt, nr

9/2001) on February 25, 2001. The motion itself was expediently eliminated by

an anti-motion put to the General Assembly with the full consent of the

leadership and was accordingly not discussed and dealt with it at all. For

further details see my foreword to The Principles of the Anthroposophical

Society and my forthcoming book on the Kardeiz Saga A Union of People.